Let me be very clear: For most of my life, I have not liked vibrato. It’s even safe to say that from age 9 to almost age 60, I have been afraid of the whole idea of vibrato. I didn’t like using it, I didn’t like listening to it and I was mostly just down on it. Below I’ll tell you a little bit about where that fear came from.

Partly because of stereotypes like this—but now, I see, largely because of ignorance and fear and misunderstanding—I have lived most of my life with a skewed impression of singers’ vibrato and just didn’t really want to think about it.

But in the last few years, especially in 2025, I have had a change of heart—a big one—and I’m not going back.

* * * * * * *

What the heck is vibrato, anyway?

Let’s start with the definition:

Vibrato is a natural, rhythmic and subtle oscillation or fluctuation in the pitch of a sustained vocal note, which adds warmth, expression and emotional depth to a singing performance. It occurs when a singer is relaxed, using healthy techniques, and is a result of the voice being in balance.

This is an oversimplification because vocal sound is a complex thing including overtones and amplitude in addition to pitch or frequency. If you want to geek out on this stuff, here’s a YouTube video of a discussion between singing teacher and vocal coach, Alexa Terry, and John Nix, Professor of Voice and Voice Pedagogy at The University of Texas, San Antonio.

String players use vibrato (most of them, anyway, at least in the Western classical tradition), and if you imagine Yo-Yo Ma or Itzhak Perlman playing, you can imagine the fingers of their non-bowing hand providing the vibrato on the neck of the instrument.

* * * * * * *

A little personal history now:

From the age of nine, I was indoctrinated against vibrato by Chris Moore, the founder of the Chicago Children’s Choir, who wanted us to sing in “head voice” with a “front face mask” focus so that we would sound like the Vienna Boys Choir. That was strike one against vibrato for me. Strike two was the explosion of the “early-music” scene in Chicago, where so many vocal ensembles that were performing the music that I loved—stuff from the 13th to the 17th centuries—were pursuing a sound ideal with virtually no vibrato, especially from their sopranos. Strike three was the fact that I never really got into opera; if I had, I probably would have enjoyed hearing a lot of glorious singing, which would have meant I’d have developed some appreciation for beautiful vibrato in vocal lines. But that didn’t happen.

In the early music world, at least at the time, the bias was for an almost completely vibrato-less aesthetic, as in what you might hear from the Tallis Scholars, the Hilliard Ensemble, Gothic Voices, or some of the other great ensembles that got going in the 1980s or so. (The great David Munrow from the Early Music Consort of London—which, by the way, mostly kick-started the early music movement in England—didn’t insist on a no-vibrato approach; perhaps partly because of this, his recordings leap out of the speaker with unbridled enthusiasm.)

In the early music world, at least at the time, the bias was for an almost completely vibrato-less aesthetic, as in what you might hear from the Tallis Scholars, the Hilliard Ensemble, Gothic Voices, or some of the other great ensembles that got going in the 1980s or so. (The great David Munrow from the Early Music Consort of London—which, by the way, mostly kick-started the early music movement in England—didn’t insist on a no-vibrato approach; perhaps partly because of this, his recordings leap out of the speaker with unbridled enthusiasm.)

There are advantages to this no-vibrato approach in some ways. Some things with tuning become easier, assuming that your pitch is good to start with. As the low bass in most of my ensembles, I tried to lay down a super-clean overtone series that would make it easy for the other singers to lock into the chord, like this from Chicago a cappella singing the Credo from Forestier’s Missa Baises moy.

Listen to the whole thing if you like, but especially the very opening, and also the chords at the 2:51-3:11 mark (we created a really great chord there at the end of that section of the prayer). It’s wonderfully delicious Renaissance sacred music. By the time we did this recording in 1998, I had been singing early music in earnest for twenty years already. I was super happy because the recording got very good reviews, and I felt like the approach to vibrato (basically none in early music) was being affirmed, along with the way I was singing most of the time.

I also had a bias against vibrato because, well, some people’s vibrato is not so beautiful. You have probably heard the joke: “Oh, that person’s vibrato is so wide, you could drive a truck through it!” In my insecurity, I used this joke at someone else’s expense to be dismissive of the whole idea of vibrato.

As it turns out, this approach with little to no vibrato works pretty well in choral music for some things, but not all things, and not all of the time. And certainly not when you’re venturing out into more solo singing. That’s when things changed quite a bit, at least for me.

* * * * * * *

Since 1998, when Chicago a cappella released the Forestier album, I’d been singing low bass and leading the high-holiday choir of eight professional singers at Congregation Rodfei Zedek in Hyde Park. Then in 2012 or so, the president of the synagogue board called. He asked me to lead high-holiday services, taking over when Cantor Julius Solomon (now of blessed memory) would be retiring. I was honored and humbled to be asked, and I spent a year working on the repertoire with Julius and on the Hebrew with Rabbi Elliot Gertel. I was also studying voice at the time, on and off, and working really hard to get technically in shape. I did pretty well for a first-time chazzan. My lessons at the time weren’t so focused on vibrato per se, more on airflow, which is a different, but of course related, aspect of singing.

Things really changed for me in 2017 when I went to China with Philip Brunelle and the International Federation of Choral Music, which put on the first-ever (and probably only ever) International Choral Folk-Song Festival in Kaili, a small city in Guizhou Province of what they call Southwestern China. That festival is a topic for a different blogpost; it was one of the wackiest, most intense, and most interesting weeks of my life. There I finally met Karen Brunssen in person. At the time, she was the president of NATS, the National Association of Teachers of Singing, a famous body of voice teachers at the college and university level. Karen teaches at Northwestern. She also lives in Westmont, so I can take lessons 10 minutes from my Downers Grove residence—super easy for me. She and I sometimes chuckle when I’m in a lesson, saying, “How strange that we had to go halfway across the world to finally meet in person!”

I started taking very occasional lessons from Karen late in 2017, and they helped for sure. She loves our older-adult choirs and, since she’s an international expert in the mechanics of the aging voice, she wrote about us in her book, The Evolving Singing Voice. And then, after I noticed that my 2024 synagogue singing had improved yet again, I got really serious and invested in one voice lesson a month for pretty much all of 2025.

* * * * * * *

Now, for context, I’ve taken voice lessons on and off since I was 17 or 18, but nobody had ever told me this:

Big Learning #1: “Your vibrato is too slow.”

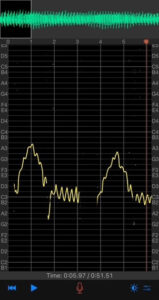

My vibrato was about 4 to 5 cycles per second, and Karen said that it needed to be more like 6 to 8 times per second. Uh, sure, okay, but how do I speed it up? Well, that has been the focus of my lessons for most of the last year. Karen has given me a few vocalizes—and those of you who’ve been in rehearsals with me have heard them and done them yourself—that help energize the vibrato and get it spinning faster. There are apps for cell phones that can show you the speed of your own vibrato. Here’s a screen shot of my singing at home the day before Yom Kippur: this is me singing a scale 1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1 and then holding the last note, on the syllable “dé”.

My vibrato was about 4 to 5 cycles per second, and Karen said that it needed to be more like 6 to 8 times per second. Uh, sure, okay, but how do I speed it up? Well, that has been the focus of my lessons for most of the last year. Karen has given me a few vocalizes—and those of you who’ve been in rehearsals with me have heard them and done them yourself—that help energize the vibrato and get it spinning faster. There are apps for cell phones that can show you the speed of your own vibrato. Here’s a screen shot of my singing at home the day before Yom Kippur: this is me singing a scale 1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1 and then holding the last note, on the syllable “dé”.

You can see here that the spin in the final note is right around the 6-cycles-per-second mark, and usually after I’ve been singing for 10 or 15 minutes I get into a groove where the vibrato is more or less reliable.

Karen also gave me the following adage:

Big Learning #2: “More vibrato, all the time.”

Say what now? No, really, you have to start the phrase with the tone spinning and keep it going all the way through.

And I have to do it at that 6-cycles-per-second speed, all the time. Ugh. That sounds really hard. And I can tell you that it takes work—constant work, constant vigilance, unbroken attention to breath and spin and the continuity of the line overall.

The good news is that it is totally worth it. I just got through the best high holidays of my life as a cantor. Everyone said I sang well, which I appreciate; but for the first time I could tell myself, without having to ask anyone else, that I was on my A-game and the line was spinning pretty much all the time.

Partly because these skills are still relatively new and partly just because high holidays are physically demanding, it took everything I had. I left it all on the floor, including going back to synagogue half an hour early for the final service so I could vocalize once more and get the vibrato to the speed it needed to be, so that I could get through that last push in a way that was healthy. Until this year I’ve gotten to that closing service (“N’ilah” in Hebrew) feeling pretty vocally shredded, trying to get through it by producing sound in any other way than simply trying to keep that vibrato in the sweet spot. Not this time.

* * * * * * *

I am very proud and grateful and just so appreciative that I have a teacher who could penetrate my thick and stubborn skull with her expertise and persistence. Once this vibrato stuff started to make sense in a more concrete way, I actually have enjoyed my own voice, taken pleasure in it and it is more like a friend with whom I spend time: “Oh, how are you today?” Sometimes singers will refer to “the voice” in the third person, as opposed to “my voice,” partly because the voice really is its own being, with its own personality, its own needs and joys and feedback loops, its rewards and challenges, its demands for attention and so on.

Now that you’ve read this, if you’re in rehearsal and you hear me (or any of our conductors) talking about vibrato, hopefully you’ll have a little more context for what we are talking about. If you’re in another one of our older-adult ensembles, or even if you’re not singing with Sounds Good Choir or Good Memories, but rather an interested member of our wider community, I hope this has been useful (or at least entertaining). Please feel free to leave a comment here and we can have a conversation about it! I enjoy hearing from you.

Love your vibrato!

Thank you for the positive note on Vibrato. I always thought it was bad. I sang with Mennonite ladies in Pennsylvania who had very wild and loud vibrato… and it sounded awful and out of control. Now I’m intrigued. I will accept a vibrato…